My Research

Dissertation:

“Trying to Pick Your Battles: Prioritization Decisions in Multifront War

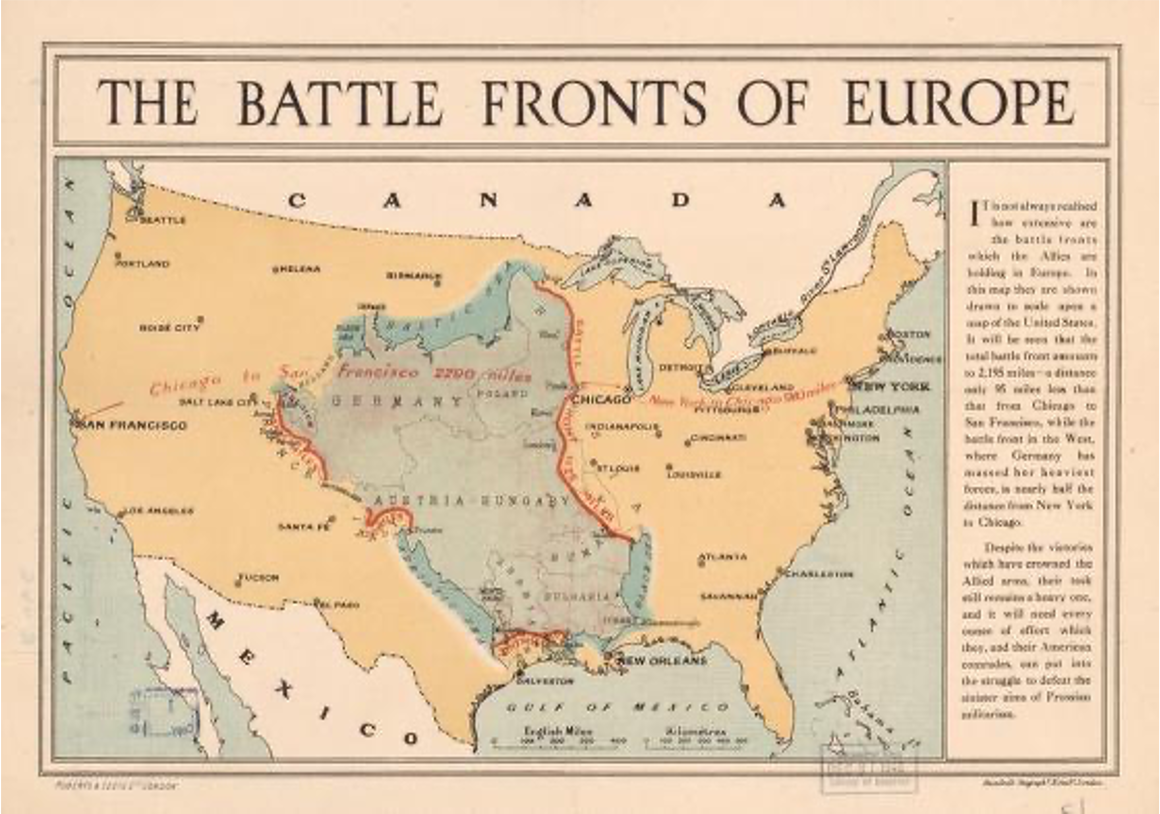

Fighting in multiple locations forces a state to divide its military, making it more difficult to achieve victory and increasing the risks of military defeat. My dissertation examines how states fight multifront wars, and seeks to explain why states prioritize different fronts, and why those prioritization decisions change. I use a combination of archival materials, memoirs, published primary sources, and secondary histories to analyze multifront prioritization decisions in Germany from 1914-1918, India from 1947-1949, and Israel from 1967-1973, arguing that prioritization decisions are based on state leaders responses to minimize battlefield vulnerabilities, exploit battlefield opportunities, and then pursuing overall grand strategic goals.

Other Research:

How States Fight

My second core interest is decisions states make around how to conduct their wars. With co-author Nicholas Blanchette, we explore this question by asking whether states can learn from the failures of their opponents. We focus on the case of the air offensives from 1939-1941 to argue that cognitive biases hamper learning from an opponent. Using material from British and American archives, we propose that perceiving opponents as a hostile outgroup or as technologically and doctrinally distinct caused members of the Royal Air Force and the US Army Air Force to discount potential lessons for their own operations from the failures they observed of the German air campaign against the UK. This project was named the Graduate Semi-Finalist for the Bobby R. Inman Award for Student Scholarship in Intelligence Studies in 2023.

Another project in this research stream focuses on “human wave” tactics in modern war.

How States Escalate

My third core interest is state decisions around escalating or limiting conflict. In this stream, I have two ongoing projects. First, I conduct a survey experiment to determine the differences in American public opinion regarding escalation in response to attacks on U.S. troops versus in response to attacks on private military contractors. Second, I examine the tension between armed bargaining and weaponizing risk in crisis signaling. Looking at cases such as the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the Cuban-South African confrontation in Angola, I argue that the military steps to weaponize risk are in direct contradiction to the military steps needed to send clear and coherent signals.